There is an Affinity, video installation___videoinstallation

- 2019

- Installation

- Video 20′45

- Video 13′12

- Video (mute) 18′

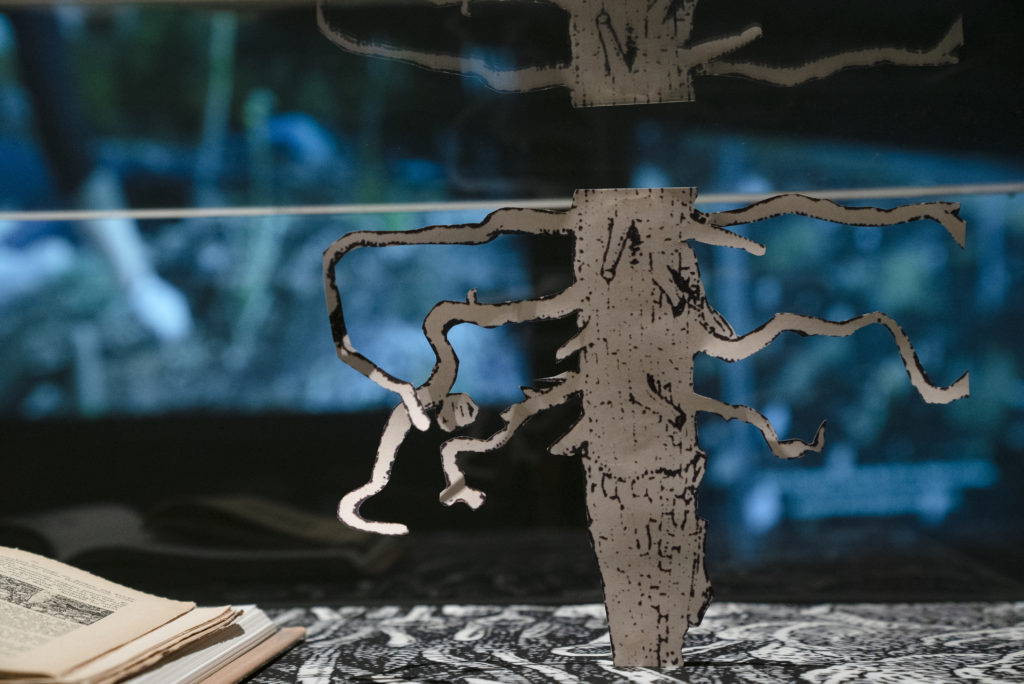

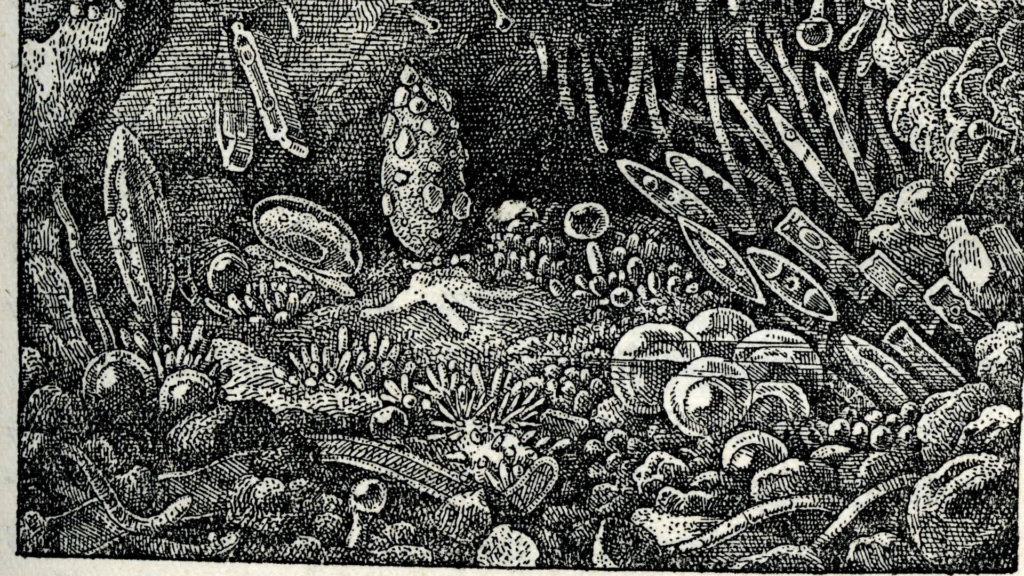

- Vitrine displaying books, a model and an enlarged detail of an illustration of microorganisms by R. H. France.

- 2019

- Installation

- Video 20′45

- Video 13′12

- Video (mute) 18′

- Vitrine displaying books, a model and an enlarged detail of an illustration of microorganisms by R. H. France.

(German version below/Deutsche Version unten.)

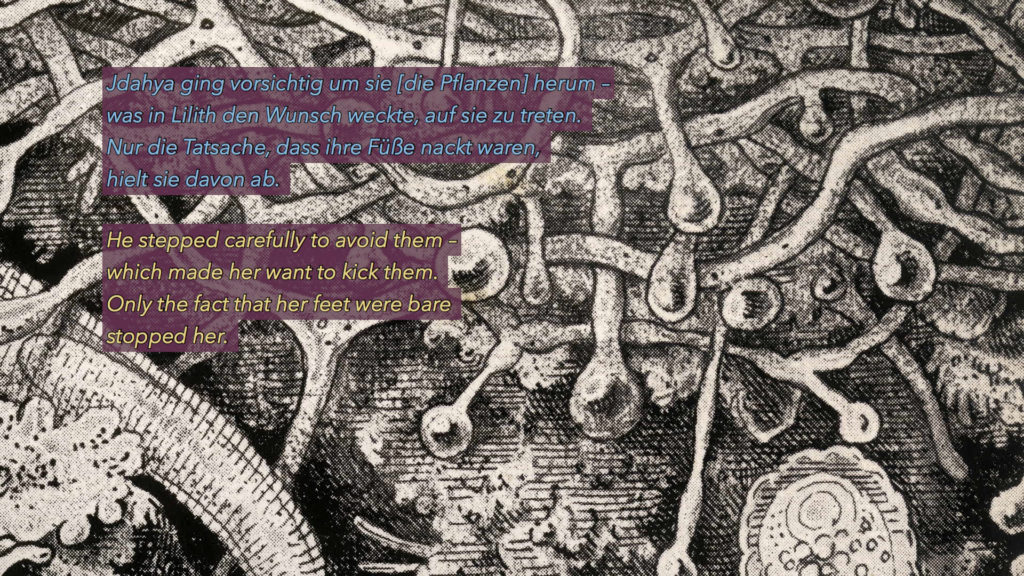

She walked beside him, silently ungrateful. Knee-high tufts of thick fleshy leaves or tentacles grew from the soil. He stepped carefully to avoid them—which made her want to kick them. Only the fact that her feet were bare stopped her. Then she saw, to her disgust, that the leaves twisted or contracted out of the way if she stepped near one—like plants made up of snake-sized night crawlers. They seemed to be rooted to the ground. Did that make them plants?

“What are those things?” she asked, gesturing toward one with a foot.

“Part of the ship.”

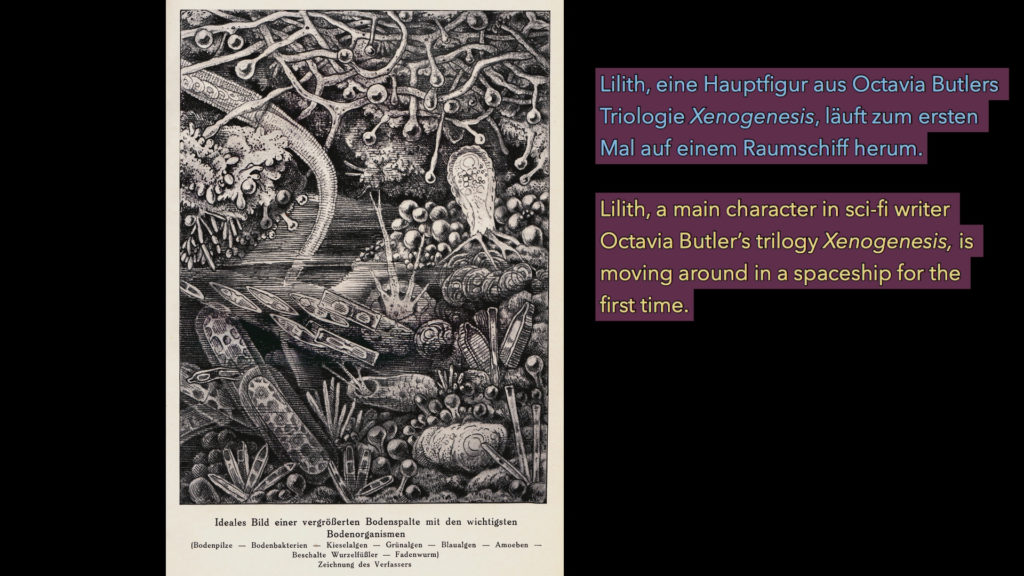

Yes, we could refer to them as plants. But in the case of There is an affinity, these beings are also part of the spaceship that Octavia E. Butler brings to life in her novel Dawn, just as the small and large worlds of the Botanic Garden, just as they also are a part of Raoul H. Francé’s microcosms, or, just as these kinds of worlds are also part of the plants—all and more.

The everyday manual activities of the gardener Brigitte Kanacher-Ataya and her colleagues, who carefully use their awareness, their senses, and their experience in working with the plants of the Botanic Garden Berlin, give us a picture of the challenges that plants impose when they are placed in accustomed as well as in unaccustomed relationships—whether it is about protecting their existence, presenting their characteristics, or making them accessible to research. Through our views, focusings, and imaginations, we get an idea of this.

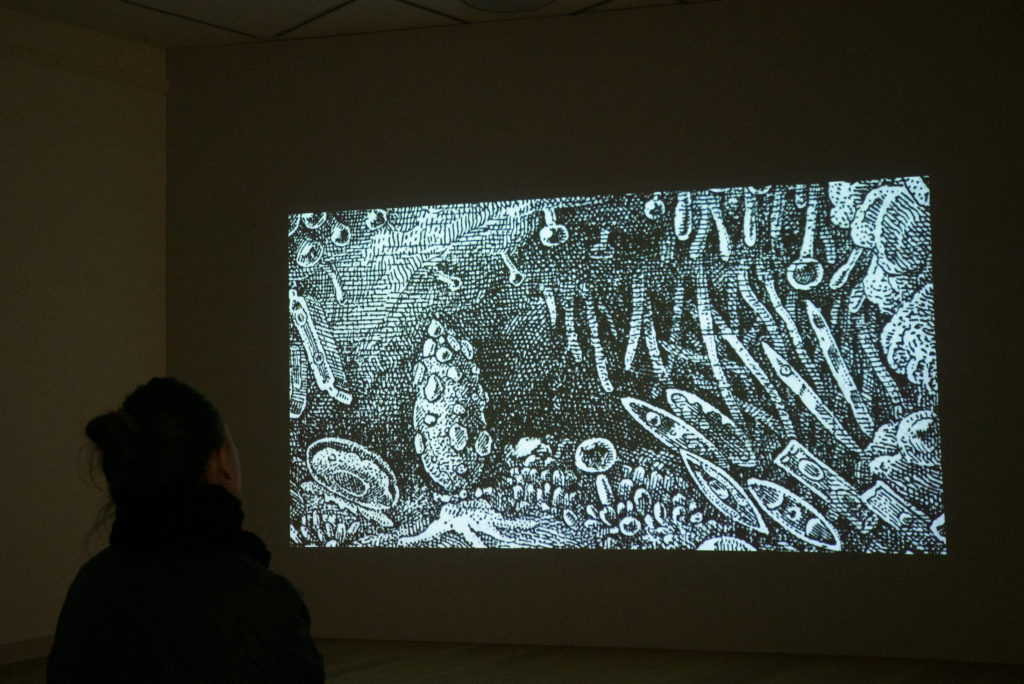

Because I focus, I overcome distance, a distance between objects, images, spaces, beings, and worlds. I not only set up a relationship between that which is captured and our sensibilities, such as thinking, but I also introduce myself. I delve into it and form an image of a reality. This becomes effective when the objects no longer only shimmer through, such as with a distant view of a diorama, rather the different layers merge into a single image. Then one also can set up proximities between the translucent images in the Botanical Museum, the landscapes through which Lilith, silently ungrateful, wanders in Butler’s novel, Francé’s detailed plant illustrations, and Kanacher-Ataya’s garden work. They are all universes, connected with one another in Gitte Villesen’s four-part video and photo installation.

—Jyl Franzbecker

The work is a commision for the project Licht Luft Scheiße. Perspectives on Ecology and Modernity at NgBk, Botanischer Garten und Botanisches Museum Berlin and Nachbarschaftsakademie at Prinzessinnengarten, Berlin.

—

Deutsche Version

She walked beside him, silently ungrateful. Knee-high tufts of thick fleshy leaves or tentacles grew from the soil. He stepped carefully to avoid them—which made her want to kick them. Only the fact that her feet were bare stopped her. Then she saw, to her disgust, that the leaves twisted or contracted out of the way if she stepped near one—like plants made up of snake-sized night crawlers. They seemed to be rooted to the ground. Did that make them plants?

“What are those things?” she asked, gesturing toward one with a foot.

“Part of the ship.”

Ja, wir könnten sie als Pflanzen bezeichnen. Aber im Fall von There is an affinity (Es gibt eine Affinität) sind diese Lebewesen ebenso Teil des Raumschiffs, das Octavia Butler in ihrem Roman Dawn inszeniert, wie der kleinen und großen Welten des Botanischen Gartens, wie sie auch ein Teil sind von Raoul H. Francés Mikrokosmen oder derartige Welten auch ein Teil der Pflanzen sind. All and more. Die alltäglichen und händischen Tätigkeiten der Gärtnerin Brigitte Kanacher-Ataya und ihrer Kolleg*innen, die ihre Aufmerksamkeit, ihre Sinne und Erfahrungen behutsam in ihrer Arbeit mit den Pflanzen des Botanischen Gartens Berlin einsetzen, zeigen ein Bild von den Herausforderungen, die Pflanzen stellen, wenn sie in gewohnte wie ungewohnte Zusammenhänge gesetzt werden – sei es, um ihr Wesen zu bewahren, ihre Besonderheiten darzustellen oder sie der Forschung zugänglich zu machen. Mit unseren Blicken, Fokussierungen und Imaginationen bekommen wir eine Ahnung davon.

Indem ich fokussiere, überwinde ich Distanzen. Distanzen zwischen Objekten, Bildern, Räumen, Wesen und Welten. Ich stelle nicht nur eine Beziehung her zwischen dem Herangeholten und unserem Empfinden wie Denken, sondern ich stelle mich auch vor. Ich mache mich bekannt und bilde mir ein Bild einer Wirklichkeit. Diese wird wirksam, wenn auch die Gegenstände nicht mehr nur durchschimmern – wie beim entfernten Blick auf das Diorama –, sondern sich die verschiedenen Ebenen fokussierend zu einem einzigen Bild zusammenfügen. Dann lassen sich auch Näheverhältnisse herstellen zwischen den Durchscheinbildern im Botanischen Museum, den Landschaften, die Lilith silently ungrateful in Butlers Roman durchwandert, Francés detaillierten Pflanzendarstellungen und Kanacher-Atayas Gartenarbeiten. Sie alle sind Kosmen, die Gitte Villesens vierteilige Video- und Fotoinstallation miteinander in Bezug setzt.

—Jyl Franzbecker